Sample Issues and Barriers to Gifted Educational Involvement

Learn more about the perceptions from CLED families regarding gifted educational involvement, the referral process, and advocacy.

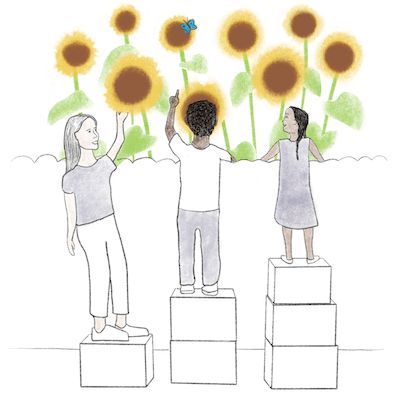

Giftedness occurs in all ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic groups; however, children from white and Asian backgrounds tend to make up the majority of gifted programs in the state of Texas. We must focus our attention on widening the net to include all students who show a high potential for giftedness and provide them with the opportunities to succeed in a more challenging academic environment. Understanding some of the issues surrounding this discrepancy, and becoming more knowledgeable about students overlooked, can assist with better identification of culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse (CLED) students for G/T services.

The identification and dismantling of barriers must be included as part of the definition of equity since the road to identification for gifted services contains several barriers for CLED students. Some of these barriers include the following:

Dr. Donna Ford, in her book Recruiting & Retaining Culturally Different Students in Gifted Education, creates a table containing more issues and barriers for culturally different families, where she explains some perceptions from CLED families regarding gifted educational involvement, the referral process, and advocacy.

Learn more about the perceptions from CLED families regarding gifted educational involvement, the referral process, and advocacy.

Equity and Inclusion guide for municipalities.

Educators may unknowingly allow biases to hinder their perception of giftedness in CLED students. The three theories surrounding cultural differences (cultural deficit, cultural conflict, cultural difference and their implication on identification for G/T services) are described below.

Individual or member of a different group is viewed as inferior due to culture and/or genetics.

Student’s environmental factors result in weaknesses in skills, knowledge, and behaviors that contribute to lower school performance. Perception is that student is not a viable candidate for G/T services.

Individual or member of a different group must navigate different cultural climates in school and home. Culture shock and clashes may arise leading to a myriad of reactions—miscommunication, misunderstanding, frustration, confusion, and so forth.

There may be a clash of values when various cultural groups have different ideas of acceptable behavior. The dominant (educational) culture determines the expectations and acceptable behaviors. After G/T identification, students are placed with teachers who do not understand or respect their cultural values and beliefs resulting in a negative experience for the students.

Individual or member of a different group is viewed as different. No culture or cultural group is viewed as superior or inferior. Every group has culture. Suspends (negative) judgments about differences, choosing instead to recognize that culture is real, as are differences.

Differences are viewed simply as differences, not deficits. Educators have knowledge of cultural differences and are more effective in seeing gifted potential. After G/T identification, students are placed with teachers who value retaining CLED students in gifted programs.

We must educate ourselves on the various cultural differences of the students in our classrooms and schools to become more proficient in uncovering the potential of CLED students. We must recognize some of the different characteristics they may possess as gifted potential, not deficits. In their book Differentiation and the Brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner-Friendly Classroom (2nd edition), Sousa and Tomlinson recreate a table illustrating cultural tendencies and beliefs that may influence a student’s learning. As educators, it is important to consider our placement on the continuum and recognize how our teaching may positively or negatively impact our perception of a student from another culture who lands on the other side of the continuum.

“There is no such thing as fate.”

“We make our own luck.”

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

“Life is what you make it.”

“Fate plays a major role.”

“People have little control over external circumstances.”

“Life is what happens to you.”

“Destiny controls us.”

“Time is fixed.”

“Schedules and deadlines are important.”

“Time and schedules are fluid.”

“Time is bent to meet people’s needs.”

“People are individuals.”

“Words carry meaning.”

“It is important to be explicit.”

“People are collectivistic.”

“It is not necessary to spell things out.”

“What is not said is important.”

“People say what they mean and mean what they say; there is no need to read between the lines.”

“No means no.”

“People are more likely to imply what they think rather than to directly say it.”

“Yes may mean maybe or even no.”

“Impartiality matters.”

“Be objective.”

“Try not to let feelings intrude.”

“Look out for members of your group because the system isn’t fair.”

“Feelings matter.”

“Relationships matter.”

“People do one thing at a time.”

“Avoid interruptions.”

“It is rude to be late or to keep someone waiting.”

“People do many things at once.”

“Interruptions are part of life.”

“It is not a problem to be late or to keep someone waiting.”

Used with permission. From Differentiation and the Brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner‐Friendly Classroom (2nd ed.) by David A. Sousa and Carol Ann Tomlinson. Copyright 2011, 2018 by Solution Tree Press, 555 North Morton Street, Bloomington, IN 47404, 800.733.6786, SolutionTree.com. All rights reserved.

The achievement gap in underrepresented students, which upon reflection is an opportunity gap between teaching and student needs, requires we not look at CLED students through a deficit lens (the habit of interpreting cultural and racial difference as a lack of ability); instead, we focus on the areas of strength and potential. To see some of these differing characteristics among CLED students, click on the appropriate links:

Table consisting of Ford’s Characteristics of Black (African American) Students, Hurston’s Characteristics of Negros, and Boykin’s Afrocentric Cultural Styles.

Gifted ELs are sometimes overlooked during the identification process. Among the barriers to identification are the following:

It is helpful for teachers to recognize the many ways giftedness exhibits itself in EL students. The following descriptions will help teachers see the abilities of EL students within their classrooms:

Exploratory Study on the Identification of English Learners for Gifted and Talented Programs by the National Center for Research on Gifted Education (NCRGE) at the University of Connecticut. Published by the National Center for Research on Gifted Education, University of Connecticut June 2018

A “twice-exceptional learner” (also known as 2E) is a child or youth who performs at—or shows the potential for performing at—a remarkably high level of accomplishment when compared to others of the same age, experience, or environment and who:

…and who also gives evidence of one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility (IDEA, 2004) (300.8) (Section 504) criteria such as:

Twice-exceptional learners do not form a simple, homogeneous group; they are a highly diverse group of learners. The contrast between their strengths and challenges may result in negative perceptions by adults, peers, and self.

Twice-exceptional learners do not easily fit into gifted education or special education programs. They are not always viewed as belonging in G/T education, but they possess many of the traditionally identified characteristics of gifted learners. They are not always viewed as belonging in special education, but they have some of the characteristics of students with disabilities. At times, their disabilities may mask their ability to be traditional producers.

The characteristics discussed should be viewed as those that are typical of many learners who are gifted and who also have a disability, rather than characteristics that all such learners possess.

Common characteristics of 2E students.

Students who are twice-exceptional may exhibit behaviors that may mask their needs for G/T services.

Document that details what Twice Exceptional students may need based on behaviors that the student demonstrates.

Cultural variations in learning are not the only considerations when looking for gifted potential. Societal myths and disinformation have been refuted over the last 20 years by neuroimaging technology. The research shows that children’s brains function similarly regardless of gender; however, because educators, parents, and society in general remain influenced by outmoded or unquestioned educational practices, gifted students may be prevented from showing their true learning potential. In younger children the damaging long-range consequences for attitudes or behavior in school are more notable. Both genders follow biologically determined timetables, specific to each individual, while the brain development is remarkably similar.

Male brains include a larger area associated with spatial-mechanical function, while only using half the brain space girls use for verbal-emotive functions. This creates a desire to move items through the space around them, such as balls, pencils (as rockets), or their own limbs. Because less blood flows to their brain, boys compartmentalize or structure learning, which affects the ability to multitask and transition between activities. Boys have less serotonin and oxytocin, which increases physical impulsiveness and an inability to sit still in a classroom. The male brain also requires resting states to recharge and renew itself which may cause boys to appear to drift off in the middle of assignments or class. To remain alert, they may resort to fidgeting or other body movements. The male brain responds to stress by increasing adrenalin which creates excitement and enhanced sensorial experiences. Boys are more commonly referred for attention-deficit disorders, learning disabilities, and discipline-related problems. They also have a greater risk of dropping out of school.

Girls have an increased capacity for communication between the brain’s hemispheres. Their neural connectors are much stronger which increases memory skills, listening skills, and voice discrimination. Because girls have more brain areas devoted to verbal functioning, detailed writing and reading skills are stronger. A higher serotonin level decreases girls impulsivity levels while an increased blood flow to the brain allows for more integrated learning. The female brain responds to stress by increasing acetylcholine which can create anxiety and physical discomfort.

| Male | Female |

|---|---|

| The male brain includes a larger area associated with spatial-mechanical functioning. This larger area in boys’ brains tends to create a desire to move items through the space around them, such as balls, pencils (pretend rockets), or their arms and legs. | The female brain contains more areas devoted to verbal functioning and detailed writing. Also, their reading skills are stronger. Female neural connectors are much stronger, which increases memory skills, listening skills, and voice discrimination. |

| Less blood flows to the male brain, enabling boys to compartmentalize or structure learning. This can impact their ability to multitask and transition between activities. | Increased blood flow allows females to integrate and enhance their own learning experiences. |

| Males have less serotonin and oxytocin hormones, which may increase physical impulsiveness and an inability to sit still in a classroom. | A higher serotonin hormone level decreases girls’ impulsivity levels, which may impact response times. |

| The male brain requires resting states to recharge and renew itself, which may cause boys to appear to drift off in the middle of assignments or class. | The female brain is capable of renewing and recharging without sleep or resting states. |

| The male brain responds to stress by increasing the adrenaline hormone, which may create excitement and enhanced sensorial experiences. | The female brain responds to stress by increasing the brain chemical acetylcholine, which can create anxiety and physical discomfort. |

| Males’ auditory processing time through the ear is longer (more specifically the cochlea), which may result in them hearing less. Because of this, boys will often ask for instruction repetition. | Female auditory processing tends to increase sound sensitivity, especially to loud, sharp, and repetitive tones. |

Differences in learning preferences can be attributed to brain structure (referred to as nature) as well as social and familial background (referred to as nurture), but each plays a role influenced by multiple other factors, including health, emotions, diet, stress, sleep, anxiety, safety, motivation, and opportunity. The brain responds to enrichment, to stimulation, and to challenge. Though the brain develops more slowly in some areas for each gender, we give them experiences to use that portion of the brain. All parts of the brain must be honed and used in order for connections to form and grow, just like exercise increases muscle mass. None of these gender learning preferences should be viewed as deficits creating lower expectations for any student. Neither should any of these learning variances preclude a student from referral or acceptance for gifted services.

Blog article regarding gender-based discrimination considerations from Brookings, a nonprofit public policy organization.

Research from Carnegie Mellon University that examined the brain development of young boys and girls.

Assessment instruments and G/T identification procedures provide students an opportunity to demonstrate their diverse talents and abilities. It is important for districts to consider alternative, nontraditional, as well as traditional, means of identifying G/T students. The purpose of assessment is to discover emergent patterns from the data collected on a student which would identify this student as one who would benefit from gifted program services. The goal is to create a collage over time versus a snapshot—a one-time test score. The Texas State Plan for the Education of Gifted/Talented Students requires the collection of data from multiple sources (State Plan 2.17).

According to the Texas State Plan for the Education of Gifted/Talented Students, there are accountability standards that are garnered for assessment*:

No one source of assessment can provide a comprehensive view of a student’s abilities; therefore, a variety of assessments should be utilized to provide a holistic picture of the child. The decision of which measures to use is left to each local education agency (LEA).

Texas Education Agency (TEA) list of various assessment providers. TEA does not endorse any assessment provider; this list is for convenience only.

Here are some issues surrounding assessment and culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse (CLED) students:

If we are to achieve true equity in identifying culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse (CLED) students, we must address and remove some of the barriers facing these students. Using the same assessment with students who may perform differently may not be an equitable practice.

Finding assessments that are completely free of cultural bias is nearly impossible. Any assessment is biased based on the learning experiences of the student taking it. Even nonverbal assessments have images that may not be understood by CLED students. For example, an analogy of a house to a bedroom may not have the same meaning to a student who has never lived in a traditional house. All assessments must be scrutinized and used with careful consideration.

One way to cast a wider net for the identification of CLED students is to screen all children during one of the early years of their education (grades 1-3). Administering a non-verbal test to all students has proven to raise the identification of CLED students. Look for the top 10% or so in each demographic and refer them for additional G/T screening. Be careful not to allow a universal screener to act as a gatekeeper for any students who have been referred for G/T screening through other means such as parent or teacher referral. The use of universal screeners in addition to local norms (discussed in Placement Considerations) can significantly increase representation in your gifted program from underserved populations.

When attempting to identify more gifted English learners, look at their language level movement through English as a Second Language (ESOL) services. As you scan through student records, ask the following questions:

Based upon the information gathered and any other relevant information, the student can be referred for G/T screening or at least identified for talent development (discussed in Placement Considerations).

One more consideration for the assessment process is to provide CLED students exposure, or frontload, experiences and activities required in gifted services prior to the assessment process. These experiences and activities would focus on building language experiences for EL students in addition to promoting divergent and convergent thinking. This action helps close opportunity gaps and allows individual talents and abilities to surface. The end-goal should always be to discover those hidden “gems” sitting in our classroom that tend to get overlooked for Gifted/Talented programs.

Systematized enrichment and diagnostic thinking skills program

It is imperative that all children have the appropriate accommodations in the assessment phase to see their true potential. Any student receiving accommodations in the regular classroom is entitled to those same modifications during the assessment phase for Gifted/Talented identification.

Texas Education Agency policies and acceptable accommodations that may be used during G/T testing.

Discuss with parents and teachers regarding English learners to determine the need for Spanish assessments or interpreters to assist with the instructions and questions. Consider cultural tendencies when students are asked to answer questions orally.

Providing the proper assessment environment will ensure the results from the assessment provide the best picture of the student’s potential. Assessment proctors should make notes regarding interesting student behaviors and mannerisms during the assessment. This may provide additional information regarding assessment anomalies that can signal alternate assessments or assessment environments are warranted. The goal is to provide an assessment environment where every child can produce the results that enable the data provided to selection committees be of the utmost in reliability.

Teacher checklists or observation forms may be part of the data collected to determine whether or not a student shows gifted potential. Because people do not always see their own bias, teacher observation instruments may evoke personal bias. Some teachers may refuse to “recommend” a student because of behaviors manifested in the regular classroom that they have determined are not characteristic of a gifted learner. Culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse (CLED) students experience school in different ways and often manifest their giftedness in ways that are misunderstood or misinterpreted by teachers who come from middle class or backgrounds different from a perceived norm. In order to achieve equitable identification practices, teachers must understand the multiple identities they bring to the classroom and must be able to understand the various multiple identities that exist within the students they are observing. Parts to consider in the multiple identities making up any individual include the following:

Teachers must become culturally aware of the diverse students in their classroom and include culturally responsive practices when providing opportunities for students to show gifted characteristics and potential. As students are provided these opportunities, teachers keep record of the gifted potential or characteristics students illustrate in order to document as much information as possible on the checklist or observation forms. If warranted, rotate all children through the gifted specialist or teacher to complete dynamic assessments of children who may not have had the same opportunities as the others. Another option is to have gifted specialists visit all Title 1 classrooms to act as talent scouts. The specialist delivers instruction while the teacher watches to recognize gifted potential. It is important to keep at the forefront of your mind that the students we are looking to identify and serve exhibit a need for something other than what the regular curriculum can provide. When looking to find students who have this potential, compare students to other students of the same age, background, and environment, not to a stereotype of characteristics you think a gifted student should exhibit. As teachers become more skilled in recognizing gifted potential in CLED students, then the shift from deficit mindset to talent scout will change the trajectory of many students. CLED students missing from proper gifted identification will finally be receiving appropriate and equitable gifted services.

The Texas State Plan for the Education of Gifted/Talented Students contains two accountability standards that relate to parent communication and referral forms*:

Educating parents about gifted programs and assessment opportunities may take more effort in order to reach the parents of our CLED students. Consider an outreach to the families and communities that is tailored to families’ needs; all families have not had the same interaction with schools. Instead of expecting families to come to you, go to them and meet with them in their environment and meeting places. Partner with an organization that already has value in the community. Consider weekend meetings to reach those unable to attend on school days or nights. Refer parents to some of the resources included in the parent section of this website so they are able to view their children through a gifted lens.

Provide opportunities for translators or interpreters to contact parents offering to help those who may be struggling to complete checklists or observation forms. Parents are with their children for the majority of their first six years of life and can provide valuable input regarding gifted potential.

According to the Texas State Plan for the Education of Gifted/Talented Students, the accountability standards related to placement considerations include*:

2.18 “Based on a review of information gathered during the assessment process, students whose data reflect that gifted/talented services will be the most effective way to meet their identified educational needs are recommended by the selection committee for gifted/talented services.”

2.28 “A balanced examination of all the assessment data collected through the district’s gifted/talented assessment process is conducted and used by the selection committee in making identification decisions.”

When considering CLED students for placement in gifted programs, we must accept and understand the disproportionate representation and help them overcome invisibility or missing-ness. This invisibility occurs because CLED students are often viewed through a middle-class white lens instead of embracing how they experience and participate in school. We must be aware of our biases, culturally destructive practices, and microaggressions that hinder the identification process for any student. Remove deficit thinking and embrace the skills these students have that allow them to experience education differently. Look for ways to grant access to gifted programs for CLED students by considering the following access strategies:

Research has indicated that CLED students’ IQ scores can be 10-20 points lower than the national norm. When comparing students with others of the “same age, experience, or environment” as described in the state’s definition of Gifted/Talented, the use of national norms does not apply to that comparison. Districts, or better yet, each campus should adopt different local norming strategies for identifying Gifted/Talented students to ensure all ethnicities and socioeconomic backgrounds are eligible for gifted services. When districts have more segregated rather than integrated schools, local norms can boost gifted identification of underrepresented populations by as much as 300% (Rambo-Hernandez, 2020). Local norms allow districts to find those hidden students who would be missing from identification using national norms. When identifying the top 5% of a campus for gifted services using local norms, the district will be meeting those students’ needs for advanced curriculum. When local norms are used for district identification results, districts can develop procedures for intra-district transfers. Portability of identification is not confirmed in the new school until re-evaluation provides evidence of exceptionality according to that school’s criteria. Note: It is the district’s responsibility to explain to parents and students that identification and programming may not continue when the student transfers to another school or district.

In keeping true to identifying students who require something more than the traditional curriculum provides and comparing students from the same experience and environment, using national norms to identify which students qualify for gifted services will not assist in finding those culturally, linguistically, or economically diverse (CLED) students. The only comparison group that will help find these students is to use norms from the local student population, called local norms. Local norms may be calculated at the state level, district level (provided the district is well integrated), or campus level. According to Peters, Makel, and Rambo-Hernandez “the use of local norms … can increase the equity of advanced educational programs and services while also better achieving their stated purpose of providing additional challenge to those students who need it.” As a result, they have developed a spreadsheet to assist in this process and written articles proving the use of local norms increase identification of underrepresented students.

Research article focusing on the use of local norms as one approach to equitable gifted identification.

A downloadable spreadsheet including a step-by-step guide on the use of local norms.

Video explaining how to use of Local Norms Spreadsheet

Paper discussing the use of local norms to increase the diversity of students identified for gifted services.

Another way to increase representation in gifted programs for CLED students is to be flexible when evaluating data used for identification. For example, a district usually requires four out of five positive indicators on their profile for identification into the gifted program. Consider altering the criteria for CLED students by identifying those who have three out of five positive indicators. For those campuses containing pockets of well-identified populations, consider increasing to five out of five positive indicators.

In the case of using identification matrices, consider not overweighing achievement tests by awarding a high percentage of matrix points on those items. Look past composite test scores and find student strengths on subtests. Another consideration is to increase the weight in other items such as portfolios or whole-class experiences which may better illustrate CLED students’ gifted characteristics.

In order to provide CLED students an alternate path to G/T identification, consider the creation of a talent development program. In a talent development program students who barely miss identification into the gifted program (or whom teachers may refer) are clustered, or placed, with the gifted students. This will require you to shift your thinking from identifying then serving to serving then identifying. Students in the talent development program are provided access to divergent/convergent thinking opportunities and possibly some aspects of G/T programming. After a year or two in this environment all students are automatically screened for gifted services. When using this model, careful consideration regarding students placed in the gifted cluster classroom should be considered.

Article regarding cluster grouping to help G/T students achieve annual yearly progress (AYP).

Book that presents a roadmap for implementing, sustaining, and evaluating schoolwide cluster grouping.

NAGC supports the growth and development of G/T children. Read about some of the various types of grouping strategies used with gifted learners.

Fort Bend ISD developed the Vistas Program to identify and nurture advanced academic potential in students from historically underrepresented populations.

National Center for Research on Gifted Education (NCRGE) developed research-based tips for successfully identifying EL students for gifted programs.

Insight into the commitment from NAGC for increasing equity in gifted education programs and services.

Resource for understanding the impact of unconscious bias in schools and their effect on students.

Self assessment one on G/T identification procedures

Self assessment two on G/T identification procedures